Solar is a wonderful way to generate electricity. It does a lot of things right, my roof generates just about all the kWhs that my house needs in a given year, no transmission lines, nuclear waste, air poolution or any of that nasty stuff. But there is one issue, namely, that most of the generation is in the summer, while most of my usage is in the winter. We begin by discussing the size of this issue, then why there really is no problem, and lastly, should a problem ever arise, there are solutions on the horizon.

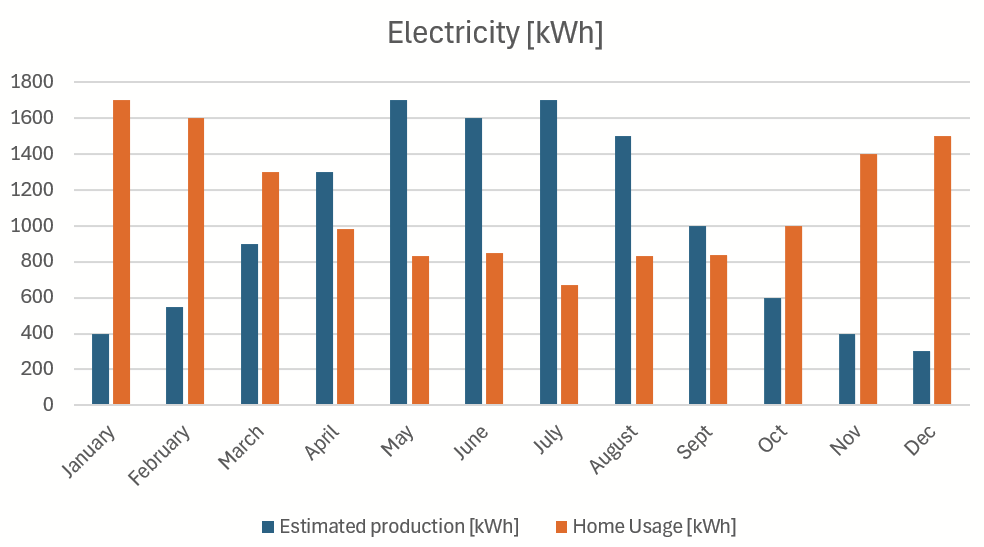

Here in the northern hemisphere there just is not as much sun around in the winter-time as there is in the summer time. Further, what sun shows up in December is often low in the sky, hence easily blocked by trees and buildings. All this means that solar production is inevitably less come winter than summer. We heat our house using a heat-pump, which uses up a lot of juice in the winter-time, resulting in our monthly electricty usage being quite a bit higher in the winter. The graph below summarizes my home production and usage on a monthly basis in kWh.

Indeed, April through September I am producing more than I am using. At the moment, Toronto Hydro happily accepts my electrons, after all, looking at historical Peak data from Ontario’s independent electrcity system operator (IESO, source) shows highest demand occuring in the summer months, usually late afternoon or early evening hours. So for now, there really is no problem, the trade with the grid works like a charm.

But suppose people actually read and believed this blog, and got solar, heatpump and an EV en masse. Well then, I suspect our IESO might have a bit of a pickel on their hands, or perhaps not, after all residential service is only about a quarter of Toronot Hydro’s electrical usage (source), with the remainder being buisiness customers and some multi-unit buildings. So, lets assume they go all in too, not only that, they magically wind up having a similar power-usage profile as me. Now we finally get to the pickle, namely that while I (and perhaps I suppose now you too), produce more energy in the summer than the winter, putting our IESO into a bit of a pickle, in perhaps a few decades.

Lets start by quantifying the problem, comparing production and home usage in the “negative” months, e.g. months where we use more than we consume, we find ourselves with a total of about 7 MWh of electrcitiy we would have to “squirrel away for winter”, about half of my homes 13.5 MWh of annual electricity usage.

Can batteries step in and solve this problem? While it is possible, if you happen to have $3M laying around you could order two Tesla Megapack 2’s (source). That price-tag seems a bit steep. Not sure if wifie would eh, approve of two shipping container sized garden fixtures.

What about hydrogen, well paired with a small fuel cell that might work. At 40 kWh/kG, Id need to stash about 175 kG of the stuff, which we round up to 200 kG. Such an amount could concievably be stored in a footprint similar to a large propane tank you find in rural Ontario, and we are now down to one shipping container sized garden fixture, that might be cheaper than $3M (source, and source). While in a rural area, with plenty of space for said tank, it might actually be a good solution (source), but we are still talking a sizable garden fixture, which wifie may not like.

Simply overbuilding the solar array is actually a good option. I’d need to quadruple the size, but it is something that could be done and might set me back perhaps a 100k or so at the $3/W peak my contractor charges. A slight problem is roof space which is scarce after I put my panels on, but since it will take many decades for us to get to this point, efficiency gains might take care of this long before we get there. The panels on my roof only convert about 20% of the solar rays into electricity. 30 % efficiency seems to be possible in the near future and perhaps by the time my panels reach their service life in 20-30 years 40% might be the norm. That’s about half of what is required, the other half might come from heat-pump efficiency gains, after all my heat-pump has a coefficient of performance (COP) of 3-4, a long ways from the 2024 world record of 39! (source), in 10 years or so when my heat pump reaches end-of-life, COP’s in the tens might be the norm, this matters as my heat-pump accounts for about half of my annual electricity usage.

One thought on “The Winter-Solar Problem”